Tiffany Calvert & Josh Azzarella

S/ample Data

Tinney Contemporary is pleased to present “SAMPLE DATA,” an exhibition showcasing the varied works of Tiffany Calvert and Josh Azzarella. Taking unique, cross-disciplinary approaches towards each piece, the artists draw from art history and anthropology while using current technology to recontextualize the imagery of the past. These reanimated cultural artifacts serve to open a dialogue into the nuances and intrigues of our ever-shifting landscape of visual media and its effect on our collective memory.

“Sample data” is a term for a data set in an experiment which is indicative of the whole. In this instance, the artists’ sample data is “existing imagery,” drawn from film and art history, which the artists then “enact experiments” upon to yield new “data” in turn. The artists’ intents are best summarized in the following question: “In what ways will the images transform, and what can that show us about how we perceive and experience?”

Josh Azzarella interrogates the processes by which images affect collective memory through various formats. Azzarella deconstructs this system of images—created and sustained by mass-media and the entertainment industry—by digital manipulation. His work manages to maintain a playful posture, while delving into the complexities of memory, history, and representation.

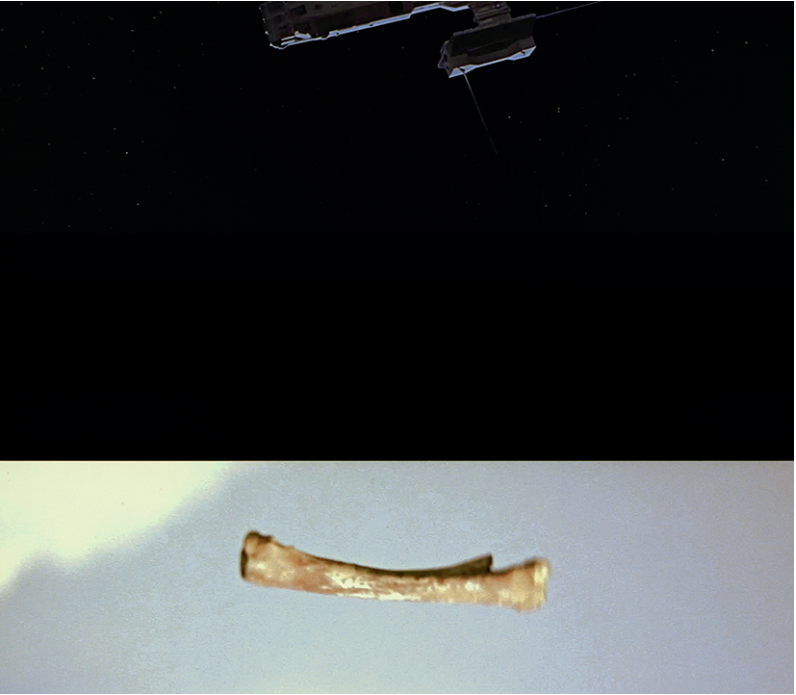

Azzarella’s installation for SAMPLE DATA includes video installation, a 3D printed object, a book, and a levitating, to-scale recreation of the Monolith as seen in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Each piece is invested in the materiality of visual media, and much of Azzarella’s work might be best understood as a translation—from images and video to sound, 2d, and 3d prints.

Azzarella connects this act of transmutation to “the apocryphal playing back of the Beatles’ Strawberry Fields to reveal a hidden message,” as he is concerned here with the “search for a new meaning in the reinterpretation of a data set through algorithmic manipulation.” Meaning is not merely fossilized and preserved but expanded; new layers of meaning are manifested by translation.

The 3d printed object is the physical manifestation of the audio created by the iconic image of HAL. The light from the image has been translated into its equivalent audio tones and as these tones play back, they have been mapped in 3d space. What results is an anthropologic study of a previous zeitgeist that remains deeply imprinted in our collective memory.

HAL, the Artificial Intelligence entity and “monster of man’s own creation,” in 2001 is an updated manifestation of Frankenstein’s monster; which was in Shelley’s time a retelling of the Greek legend of Prometheus. Here, the robot is removed from straightforward depiction. Like the monolith, Azzarella has created an index of the “thing itself,” the mythology which branches out from HAL across generations and cultures is here congealed as an abstracted visual symbol.

Likewise, the bound musical score is the result of an algorithmic translation of the film’s visuals to musical notation. The result is that the once-familiar film becomes entirely defamiliarized, out of its recognizable visual language into another. The score becomes a relic, recalling hieroglyphs or runes, maintaining lost narrativevia foreign symbols.

The monolith—a giant, mysterious stand-in for some evolutionary force or otherworldly knowledge—lies petrified in this icon. Azzarella playfully maintains the mystery (the lingering question of viewers is “how is this thing floating?”), as well as the mythological meaning granted to it by the film.

Azzarella arbitrates the relations between the signifier and the signified, the real and the representation (or re-presentation), by pointing reflexively to the arbitrary nature of media materials and of language itself. Azzarella preserves the intrigue of the original by virtue of technical genius yields a series of artifacts; a museum of our contemporary mythology. However, the contents are no mere pastiche or monument, but an altogether new vision, pieced together from the fragments of a shared mythos.

Azzarella’s installation for SAMPLE DATA includes video installation, a 3D printed object, a book, and a levitating, to-scale recreation of the Monolith as seen in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Each piece is invested in the materiality of visual media, and much of Azzarella’s work might be best understood as a translation—from images and video to sound, 2d, and 3d prints.

Azzarella connects this act of transmutation to “the apocryphal playing back of the Beatles’ Strawberry Fields to reveal a hidden message,” as he is concerned here with the “search for a new meaning in the reinterpretation of a data set through algorithmic manipulation.” Meaning is not merely fossilized and preserved but expanded; new layers of meaning are manifested by translation.

The 3d printed object is the physical manifestation of the audio created by the iconic image of HAL. The light from the image has been translated into its equivalent audio tones and as these tones play back, they have been mapped in 3d space. What results is an anthropologic study of a previous zeitgeist that remains deeply imprinted in our collective memory.

HAL, the Artificial Intelligence entity and “monster of man’s own creation,” in 2001 is an updated manifestation of Frankenstein’s monster; which was in Shelley’s time a retelling of the Greek legend of Prometheus. Here, the robot is removed from straightforward depiction. Like the monolith, Azzarella has created an index of the “thing itself,” the mythology which branches out from HAL across generations and cultures is here congealed as an abstracted visual symbol.

Likewise, the bound musical score is the result of an algorithmic translation of the film’s visuals to musical notation. The result is that the once-familiar film becomes entirely defamiliarized, out of its recognizable visual language into another. The score becomes a relic, recalling hieroglyphs or runes, maintaining lost narrativevia foreign symbols.

The monolith—a giant, mysterious stand-in for some evolutionary force or otherworldly knowledge—lies petrified in this icon. Azzarella playfully maintains the mystery (the lingering question of viewers is “how is this thing floating?”), as well as the mythological meaning granted to it by the film.

Azzarella arbitrates the relations between the signifier and the signified, the real and the representation (or re-presentation), by pointing reflexively to the arbitrary nature of media materials and of language itself. Azzarella preserves the intrigue of the original by virtue of technical genius yields a series of artifacts; a museum of our contemporary mythology. However, the contents are no mere pastiche or monument, but an altogether new vision, pieced together from the fragments of a shared mythos.

Tiffany Calvert systematically applies oil paint to large-scale, digital prints of Dutch still life paintings to create visual interruptions, pixilation, and glitches that recontextualize the works and place them in dialogue with an evolving, postmodern notion of perspective.

These floral still-lives were carried out with an almost-absurd meticulousness, depicting flowers, fruit, and near-microscopic insects crawling on stems and leaves (“ample” in the exhibition title a nod to the amplitude of visual information contained in these works). Calvert is intrigued by the wealth of visual detail as well as the symbolic meaning of the objects depicted. For instance, the Dutch Tulip varietal most prized during the 17th century “Tulipomania” (often depicted in these paintings) was the Semper Augusts, which yielded a scarlet-stiped flower. This striping was caused by a viral infection of the bulb, which also weakened the flower and eliminated its ability to propagate—its scarcity leading to higher market value.

There is a parallel here between the flower and Calvert’s work; the glitches indicative of digital decay, the loss of fidelity that comes with transmission. Yet, in Calvert’s paintings, these interruptions add to the beauty of the piece, creating resonances with the contemporary.

The picture-of-a-painting—remixed, severed from its original art-historical context—is thrust into the present chaos of overlapping and competing “picture planes.” We instead stare into “windows” (or Windows, or the latest Mac iOS) and are met with an onslaught of visual data. Even the opulent and overwhelming amount of information of Dutch photorealism pales in comparison.

The works here embody a dissonance. Calvert’s paintings are mimetic of low-res, Google search reproductions, pushed to the margins in an economy of images valued for fidelity to the original. Calvert flips this hierarchy on its head by elevating the transient, the modified, the damaged, the reproduced and remixed. And while each piece recalls the chaos of the screen, Calvert also manages an almost meditative quiet, clear to the viewer in engaging with each piece.

March 7 - April 13, 2020

︎︎︎ Exhibition List

These floral still-lives were carried out with an almost-absurd meticulousness, depicting flowers, fruit, and near-microscopic insects crawling on stems and leaves (“ample” in the exhibition title a nod to the amplitude of visual information contained in these works). Calvert is intrigued by the wealth of visual detail as well as the symbolic meaning of the objects depicted. For instance, the Dutch Tulip varietal most prized during the 17th century “Tulipomania” (often depicted in these paintings) was the Semper Augusts, which yielded a scarlet-stiped flower. This striping was caused by a viral infection of the bulb, which also weakened the flower and eliminated its ability to propagate—its scarcity leading to higher market value.

There is a parallel here between the flower and Calvert’s work; the glitches indicative of digital decay, the loss of fidelity that comes with transmission. Yet, in Calvert’s paintings, these interruptions add to the beauty of the piece, creating resonances with the contemporary.

The picture-of-a-painting—remixed, severed from its original art-historical context—is thrust into the present chaos of overlapping and competing “picture planes.” We instead stare into “windows” (or Windows, or the latest Mac iOS) and are met with an onslaught of visual data. Even the opulent and overwhelming amount of information of Dutch photorealism pales in comparison.

The works here embody a dissonance. Calvert’s paintings are mimetic of low-res, Google search reproductions, pushed to the margins in an economy of images valued for fidelity to the original. Calvert flips this hierarchy on its head by elevating the transient, the modified, the damaged, the reproduced and remixed. And while each piece recalls the chaos of the screen, Calvert also manages an almost meditative quiet, clear to the viewer in engaging with each piece.

March 7 - April 13, 2020

︎︎︎ Exhibition List